Executive search and consulting firm Spencer Stuart works closely with corporate leaders, and regularly puts together reports about the feelings of leaders and the future of leadership. After collecting data to analyze the performance of every S&P 500 CEO during the 21st century, the firm's CEO analytics leader Claudius Hildebrand and co-leader of its CEO succession practice Robert Stark, turned their findings into a deeply researched book, The Life Cycle of a CEO, which becomes available this week, explains the journey of a CEO's job. It covers the time before they are chosen for the role, and then what happens when they leave and someone else takes over.

I talked to them about their book and its lessons for leaders of all sorts. This conversation has been edited for length, clarity and continuity. It was exerpted in the Forbes CEO newsletter.

Who is this book for?

Hildebrand: This is a book about leadership. It's a book for CEOs, but it's not a book exclusively for CEOs. We just happened to choose to study leadership in its most complex form. And when you look at CEOs and the situations they encounter, that really is the perfect Petri dish where the most ambigious, most complicated questions land. The questions that nobody else dares to answer, the CEOs have to confront them. Many of the lessons learned will be applicable to anyone who's aspiring to be a leader, and obviously very helpful to all the CEOs in their day-to-day and as they navigate their careers. But the bigger point of the book is really around how do you grow as a leader, and how do you evolve over stages?

We have the benefit and the privilege through our work [to] work with many CEOs on a day-to-day basis. We have the privilege to access that group and study through their lens, but the intent has always been to share these messages on a broader basis. I was at [University of California] Berkley yesterday speaking to a group of MBA students, and they found those insights just as helpful as they are aspiring and dreaming. Not every one of them will be a CEO, but it will help them guide their actions towards those goals.

Stark: There's no doubt that CEOs are the primary targets or focus of attention, scrutiny, or criticism. We have the opportunity to work with individual CEOs, new CEOs, and long-serving CEOs. We have so much wisdom from working with those individuals, then gathering insights from the quantitative research and the qualitative. We use all of that in our work with individuals, and it seemed like the perfect moment to A: Go from working with several, to sharing with many CEOs, and B: To integrate all those into one stage-by-stage framework for development for the CEO. The CEO, I think, is audience number one.

We also, in all of our research and work, learned a lot about the years leading up to the CEO job. Those were really powerful stories that we felt like we had to tell. There was always an intention to make this accessible and helpful to people even earlier in their careers. We have that particular chapter, but the whole arc of the book is helpful for people to think about their own development.

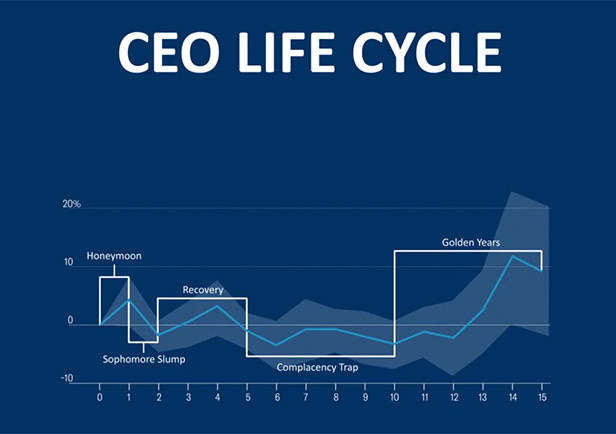

Six years ago, when we first discovered this non-linearity and the ups and downs of the CEO’s tenure, I’d been at Spencer Stuart at that time about 10 years, and the first thing I asked myself when I saw the chart was: Where am I on this chart? Am I in a complacency trap? Have I just been unwittingly settling in and not noticing that my performance and energy might be waning? Do I need to renew? Do I need to do something different? I think it has a lot of applicability for anybody where they are and as they think about what comes next.

Hildebrand: It’s very applicable to CEOs, but also those surrounding CEOs. Think of CHROs who aspire to be a confidant. It’s helpful for CHROs to understand the challenges that their leader might go through. It’s great for boards who want to empower the CEO, make them better and understand their perspective: where they can help but also inform their decision-making. It’s great for those observing leaders: the financial community, investors, the media. To understand, to take perspective and sometimes maybe even empathize a little bit with the role that they’re filling.

What made you decide to pursue this book, and where did the idea come from to write about leadership in this way?

Stark: I’ve been advising and coaching CEOs and senior leaders for a long time. It’s the thing I really love to do is to have breakthroughs with these people. To help those leaders, we as a firm and me individually, have been really determined to be able to provide more insight to those individuals, get beyond some of the myths and false ideas about what it takes to be successful. That was really what drew me into the research.

Hildebrand: I’ve always felt a deep dissatisfaction with the way we think about leadership. We all agree that leadership is an incredibly important lever to guide our societies and our fortunes. At the same time, it is all story-based. It’s all narratives, conventional wisdom. Don’t get us wrong: Stories have their place, and the book is chock-full of stories to illustrate some of the principles. But what’s really been missing is a different lens to study leadership that integrates the stories and the conventional wisdom, but also checks it through the transparency of big data.

Over the last seven years, Bob and I have been leading this effort to understand patterns over time by aggregating big data sets and studying the performance patterns of leaders and what makes them successful, to parse facts and fiction, and to validate some of these stories that are out there, and to prove those that are not so helpful, or wrong.

Both of you work with executives and leaders all the time. What were some of the things that you found through the research for this book and also talking to former and current CEOs and board members that surprised you, or stood out as being more important than you had thought?

Stark: I think the big initial surprise was from the quantitative research. We all assume—I, too, had assumed, most directors and CEOs we surveyed assumed—that once someone gets in the job, their growth, and therefore their performance, both follow a linear trajectory (A linear trajectory refers to a path or movement that follows a straight line). And the data totally upended that. It’s not linear at all.

Hildebrand: Many people think leaders are special. They believe that when someone becomes a leader, they suddenly know everything. This is not true. They’re wiser, they’re funnier, they’re taller. This is the way we portray these leaders in the media. It’s also the way we as a society want to see these leaders. We don't want a leader who doubts themselves. That doesn't make us feel very confident. It’s also in the advice that’s currently out there for leaders: This idea that you have to have these four traits, or these five behaviors and these six mindsets. What we find time and time again is when we work with executives and CEOs and advise and we [find there are some] who question their decisions, who have to rely just as much on gut as they have to rely on information. And to Bob’s point around this idea of continuous growth, we found there’s no model of leadership that focuses on a set of growth or development stages.

But at the same time, you never step into the same river twice. Just because someone is the leader doesn’t mean that they don’t change over time. And that’s what we found. The challenges that leaders face might have similarities, but they manifest themselves differently depending on where one is in their tenure, and then where one psyche is in those moments. The book’s not only about what CEOs do to be great, but it’s also how leaders feel along that journey.

If you ask people today about CEO tenure, and performance of CEOs over time, they will paint a picture of an inverted U, where each year is better than the last, until around year eight, nine, or 10, when their energy wanes and the U starts to curve down. The big reveal of the initial research was that it’s not linear at all. There are these headwinds and tailwinds, these sharp ups and downs that are, I think, for most people, completely unexpected.

__

This story is quite a long so I've decided to split it into two parts. By breaking it down, I hope to make it easier for you to follow along and enjoy each part without feeling overwhelmed. Thank you

0 Comments